| Publisher | Z-Man Games and Pearl Games |

| Design Credit | Etienne Espreman |

| Art Credit | Alexandre Roche |

| Editing and Development Credits | Sébastien Dujardin and Etienne Espreman |

| Translation Credit | Nathan Morse |

| Game Contents | Board (Brussels), Art Nouveau board (five Action strips, Bonus strip), five Architect boards, 30 Building tiles in player colors, 26 Public Figure cards, 25 Bonus cards, 12 Stock Market cards, Bracket tile, Workshop cursor, six Compass tiles, 35 Assistant pawns in player colors, 20 disks in player colors, 30 Work of Art tokens, five Exhibition tiles, 88 coins, 45 Materials cubes (30 Noble resources, 15 white Jokers), Manneken Pis pawn (first player), rules |

| Guidelines | The Rise of Art Nouveau game |

| MSRP | $64.99 |

| Reviewer | Andy Vetromile |

At the end of the 19th century, Brussels exploded with the Art Nouveau movement. Artists made the entire city a work of art both with the pieces they sponsored and the signature buildings they constructed. The natural curves melded with everything from homes to hairbrushes. That’s a lot to stuff into a single board game, but Bruxelles 1893 isn’t put off by the challenge.

The object of the game is to have the most victory points after five years worth of exhibitions.

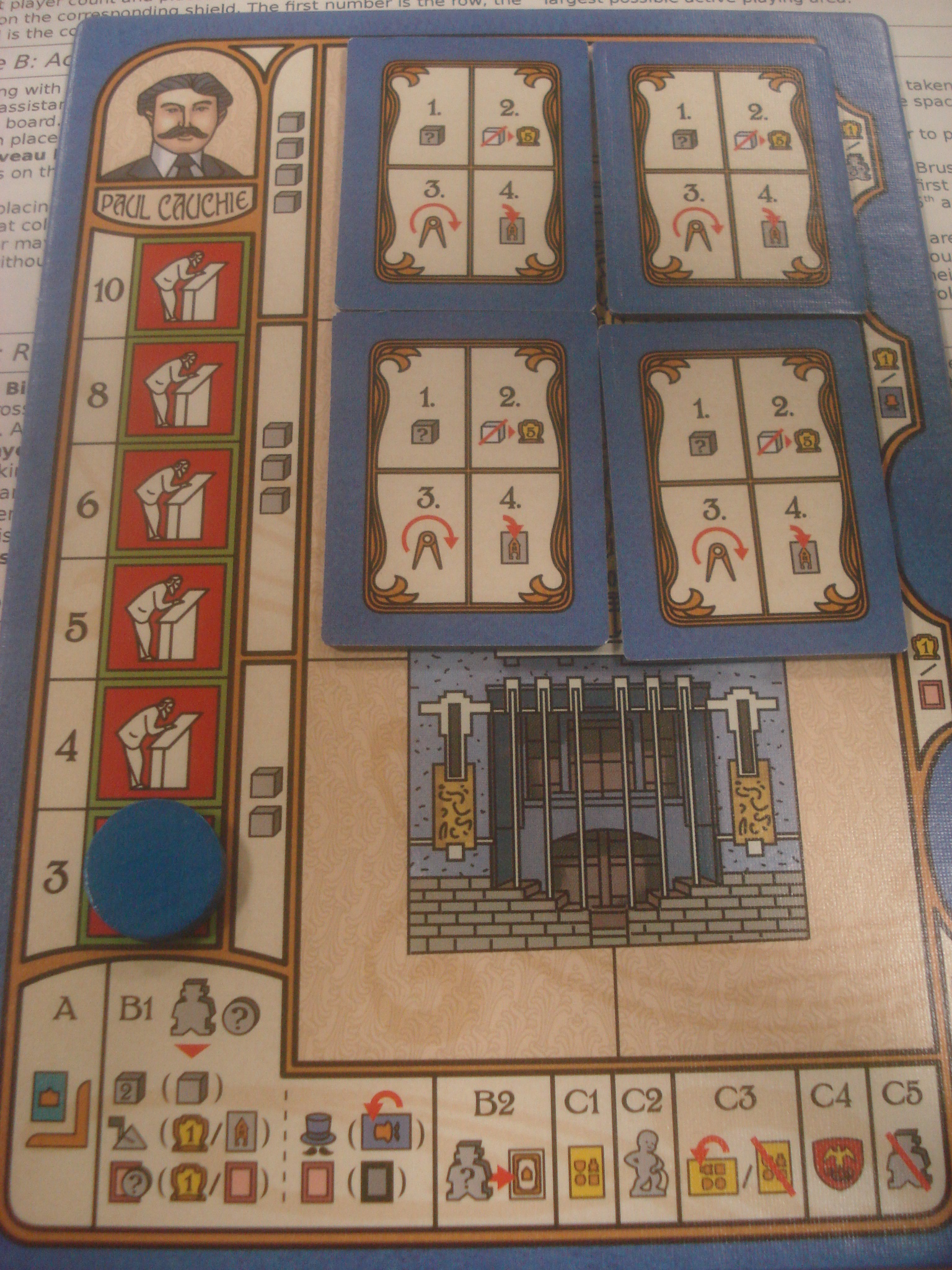

Two to five players become artists of this new style. They begin the game with money, Assistant pawns, and their Architect’s board full of fanciful building designs and in-game formulae. The main board sits in the middle of the table; half is a staggered sequence of “roles” the players can claim while the other represents the city of Brussels and all its hustle and bustle.

Yes, it looks like a street festival on the Place du Grand Sablon but it's an auction; are you in or what?

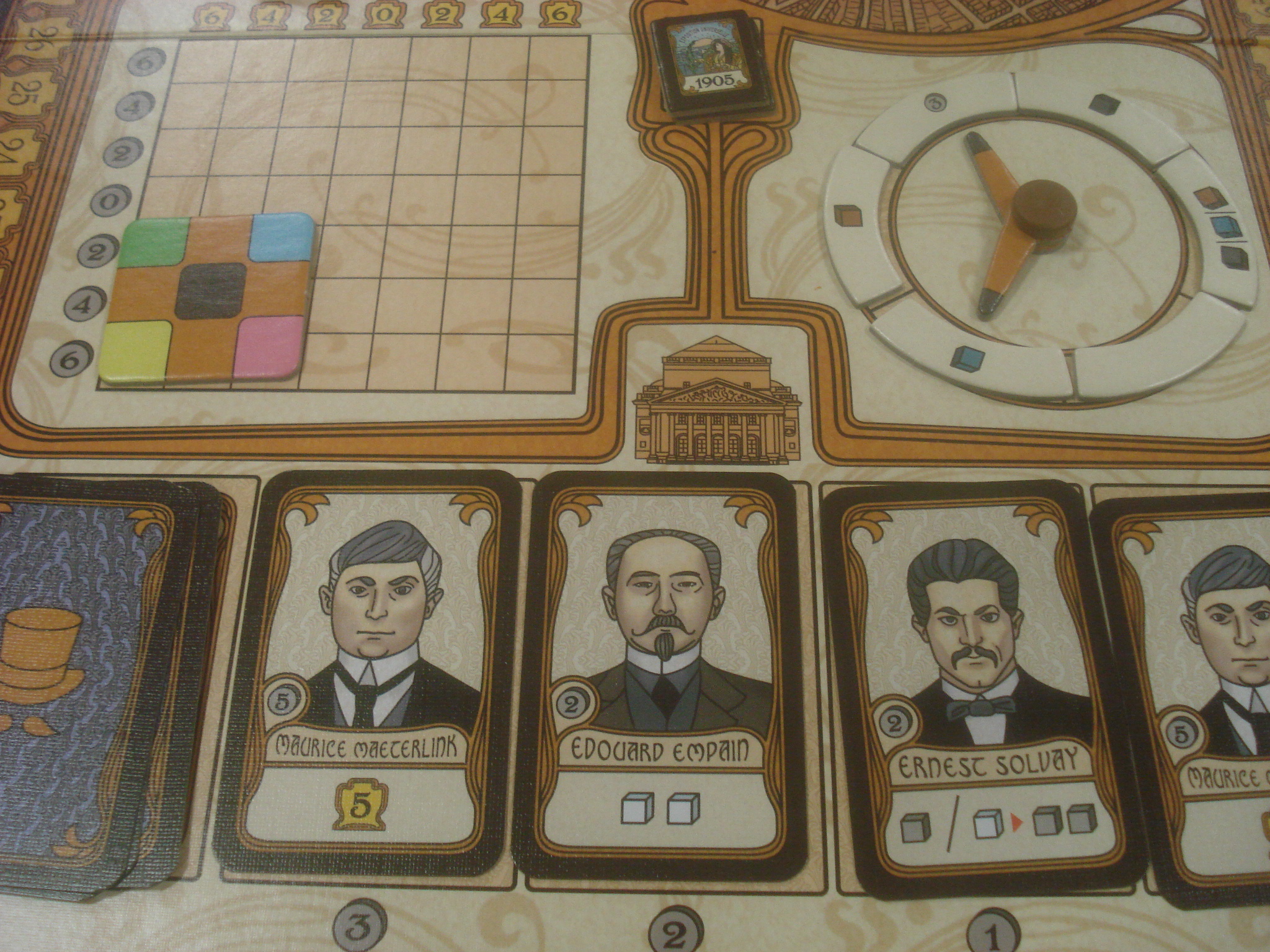

Most activity happens on the Action board, a five-by-five grid of spaces. Placing meeples on these roles allows players to collect or spend resource cubes to erect grand buildings; create or sell artwork; or engage the patronage of famous persons. It costs Belgian Francs to put Assistants here but the money improves one’s chances of “winning” that column. Each column of roles ends in a Bonus card awarded to the most lavish spender. There are also symbols at the intersections that, if surrounded by Assistants, pay out VPs. Finally, if one builds a portion of the building from his player board, the crowning achievement for each player, he places that tile piece on an unused action space – now if someone plays a pawn there he gets a small secondary reward.

Art Nouveau is part of everything, not just the architecture, so players can fund their activities by selling their paintings at the workshop. A “cursor” indicates the current value in both money and victory points for each color of art and the market can be manipulated by those with better tile collections. If the player seeks patronage, he can pay Public Figures (cards) to support his efforts with their various benefits. These gentlemen help once before being discarded unless their services are retained for the duration – but everyone so employed must receive a fee in full at game’s end to avoid VP penalties.

To skip paying for services or if all the good action spaces are taken (certain sections of the grid are designated off-limits each turn, making the middle of the board the best value), players can get the same actions on the Brussels board for free, but they lose out on the Bonus cards paying customers get as well as the VPs for surrounding the intersection symbols. Further, the first player to use a given space in Brussels places an Assistant meeple but subsequent users of the same spot expend two Assistants, then three, and so on. The final indignity: The architect with the most meeples in Brussels’ action area loses one to the Courthouse where the sneaky so-and-so has to explain his unfunded backroom actions to the authorities. Freeing these workers from red tape requires a Bonus card or Public Figure intervention.

Eventually everyone runs out of Assistants or actions, and when all have passed their turn the year ends. After five exhibitions additional VPs are awarded for things like your art collection, Public Figures, building tiles used, and number of Assistants not hung up in court; the architect with the most points wins.

The box yields a trove of swell components. Boards and counters both are good cardboard and the tokens are wooden and colorful (though the red and orange player hues are too similar for comfort). The evocative artwork precisely reflects the era’s sensibilities, but the printed information is busy and hard to digest. (Dense or not it helps having a how-to printed on everything including the building tiles.) Prices creep up in the game market but plenty of good stuff is packed in here to make it worth one’s while.

For a standard box, Bruxelles 1893 takes a chunk of tabletop real estate. The rules’ capitalization conventions are odd and they could have used another read-through (some of the straggling errors may be from the translation process). Most of the mechanics have solid visual examples throughout the booklet but the rules fail to provide them for building construction, which would have helped. The Action strips have a flip side so they can be alternated to produce less orderly options; this in turn makes bidding less methodical, but aside from referring to these as the “expert” side the rules don’t actually spell out this mechanic. The Z-Man Games website claims it’s a 90-minute game while the box says 25 minutes per player. That number tends to inflate a bit with four or five participants and can run longer than two-and-a-half hours if circumstances work against you. Since every game can be different (especially if one implements the alternated Action strips) replay value is high, but even the non-expert version isn’t something for the casual gamer.

If Bruxelles 1893 has a real fault it’s that it tries too hard. It wants to appeal at least a little to all gamers, so it ends up hitting a lot of the popular tropes: You draft cards, there’s some auctioning, some worker placement, some area control. No game can be all things to all people but there are something like five ways to score points during the game and seven more to add at the end of the game. That’s good for those who enjoy “hidden” points and greater flexibility in scoring but strategies may end up being more opportunistic than planned, especially for anyone who has trouble following all the threads to see the big picture.

Bruxelles 1893 facilitates play well. Money and resources aren’t as tight as some games, but even when they are there are clear avenues to getting what you need. Manipulating things is a lot of fun, especially with the resource “compass” that determines what is currently needed to erect buildings – this way you can either better plan your next build action or damage your competition’s chances of getting their next tile to the board. It’s hard to build up a coherent strategy, so architects need to be able to think on the fly, but at least there are multiple paths to victory. It takes a couple of games just to get used to the possible options, but one can play several times and not duplicate themselves. Bruxelles 1893 is too busy and makes play neither easy nor light, but for dedicated gamers it’s a meaty set of rules they can sink their teeth into . . . no doubt what Salvador Dali meant by the “terrifying and edible beauty of Art Nouveau architecture.”