| Publisher | Nazca Games, Inc. |

| Design Credit | Emerson Matsuuchi |

| Editing Credit | Alex Shvatsman |

| Contributing Credits | Roni Matsuuchi, Brian Lam, Elizabeth Lam, Eugene Bolotin, Jon Monath, Robert Brotherson, Alex Malyavko, Sergey Vozny |

| Game Contents | Two double-sided game boards, four player boards, four player screens, four plastic robot figures, 12 action dice in red, white, and blue, blue control point die, four sequence tokens, eight damage tokens, 19 victory point tokens, 16 module tiles, 16 mine tokens, four grenade tokens, four magnetic field tokens, four teleporter tokens, four tractor beam tokens, four reflector tokens, rules |

| Guidelines | Robot combat and racing game |

| MSRP | $44.95 |

| Reviewer | Andy Vetromile |

Remember all those TV shows where designers brought their little robots to get in a ring and chop, bludgeon, and chainsaw one another into submission? In the world of Volt they never stopped televising it, or improving on the violence. Now they employ full-size mechanical men in a no-holds-barred arena donnybrook, firing off far more dangerous weapons and keeping the masses enthralled.

The object of the game is to be the first to gain five victory points.

Two to four players take control of a robot apiece with a player board, a screen, and a trio of colored dice. Before them is the arena, a board dotted with six numbered spaces and several yawning pits. Players use the dice to program their robots’ movement and attacks but they don’t roll them, they choose the numbers to allocate to their boards behind the anonymity of the screen. Robots move in four directions and fire in eight (including diagonals).

The number of pips is the distance moved, so a three on the left movement arrow moves a robot left three spaces. Attacks operate the same way – put a die on a weapon control and the robot’s blaster fires that direction – but the shot travels until it hits something. The number in this case is the effect he wants. A one is a straight-up point of damage. A two through six, however, may also scramble an enemy’s dice program or push them one space. The trick is the dice are resolved in red-white-blue order (seems like there ought to be a mnemonic to remember that), going from lowest to highest. Low is almost always better in Volt, so if you want to act first you have to do it with the lowest numbers. You can go further or use the fancy blaster effects with higher numbers, but then chances are your opponents go first and either you’re dead metal or your target is gone (it’s frankly a shame the crazy dice effects don’t come into play more). Aiding robots in their pursuit of glory are weapon, defense, and gadget upgrades called modules. With them a robot may leave a trail of explosive mines, shove others away with a repulsion field, or teleport to trade places with other objects.

Counters clockwise from top: victory point; damage chit; priority sequence for breaking ties; module; mine; and Volt counter (in case you forget what game you're playing, apparently)

A player gets a victory point if his robot lands the killing blow on an opponent or just plain shoves the poor schmoe into a pit. Then there are the numbered areas on the board, control point spaces selected by rolling a die, and ending the turn on the currently selected space also nets a point. As soon as someone claims their fifth point they win the game. Of course, each turn ends with destroyed robots respawning, and his memory banks are not among the things lost when a robot dies . . .

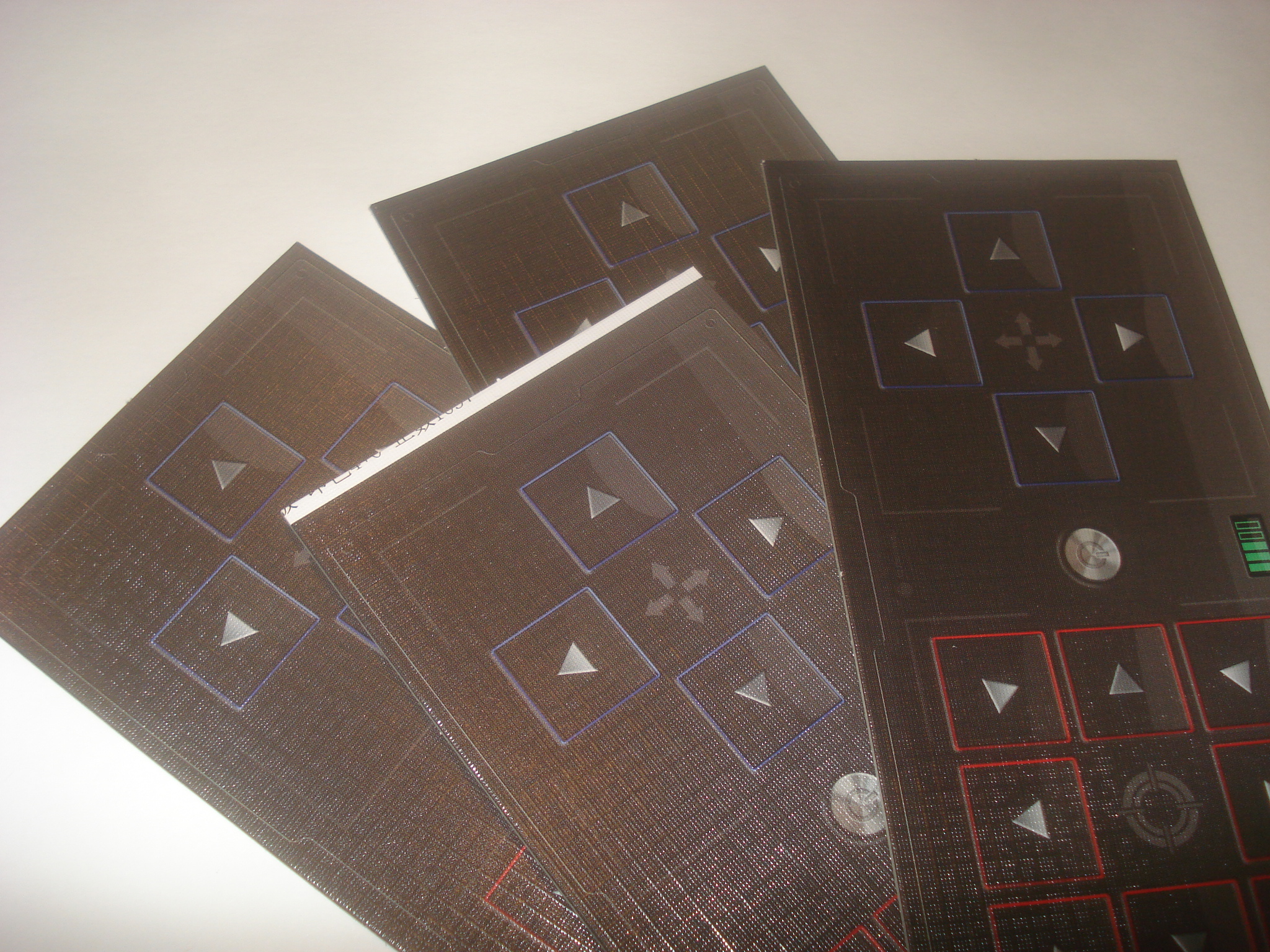

Volt’s components all perform really well. The robot figures are lightweights, in the literal and plastic sense, but they’re dynamic and posed for action. You get not one but two mounted double-sided boards with varying arena layouts – that ought to keep anybody busy – and the cardboard that accompanies them is the good stuff. The players’ boards are surprisingly thin compared to the rest of the set (and one board in the review copy is sliiightly misprinted, though not in other copies examined), but the modules, damage markers, victory points, all are good chitwork. Even the privacy screens are full-bodied additions with all the necessary rules printed on the inside. Too many games have shields that start flat, get folded, and never stay where you put them, but these are precut and offer no resistance to player use or box storage. The dice are standard plastic six-siders (with a special numeral version for the control point die – having that in a fourth color would have been preferable), and the box comes with plastic baggies for storage.

Just to confront the elephant in the room, yes, this game owes a lot to RoboRally, Richard Garfield’s original programmed-path game of robot racing, but while it’s easy to think of as RoboRally Lite they’re not the same animal. Volt is a much easier game to learn, execute, and play. The mechanics aren’t as involved, a game takes maybe half an hour, and you can get in several iterations at one sitting. This is especially helpful given all the suggestions the rules have for drafting weapon modules and playing out multi-round tournaments. You could finish an entire league “season” in one night even if you had but a few copies to pass around. It might even be too short for some tastes, but if the participants’ collective patience allows for it they can play for higher points (seldom do all the VP tokens get used anyway).

It would be nice to have more than four people in the mix but it runs as well with two players as it does with a full house. The compact size and design of everything – the 9×9 board, the easy kills, the plentiful pits – are part of the thing’s charm. The combined elements of groupthink and the lower-is-better hierarchy of operations raise some unexpectedly devious issues during planning, and the modules make life even more interesting (the rules even answer most of the questions these raise). Volt improves on its predecessor by offering a lot more interaction, maintaining the amusing combat and gallows-humor deadliness that quickly fade from Roborally with even a little skill. Conflict among automatons becomes the rule and not the exception in the intimate confines of the perilous but entertaining Volt arena.