| Publisher | Baksha Games |

| Design Credit | Sean Garrity |

| Art, Graphics Credits | Scott Tackaberry, Colton Balske |

| Game Contents | Time days board, six colored player/day markers, 130 cards (six roll charts (also in player colors), 30 $1 million notes, 12 $5 million notes, 24 10 million notes, 34 contracts, 24 specialists), 12-sided die, rules |

| Guidelines | Time travel for fun and profit contract game |

| MSRP | $19.95 |

| Reviewer | Andy Vetromile |

It’s a race through time worth millions to the right buyer, but although it’s called Time Jockeys you aren’t riding horses, you’re tripping through history with a time machine implanted in your body. And hey, welcome to TITOR Corporation.

The object is to be the richest, preferably living, time traveler.

But the two to six chrononauts involved aren’t in it for the love of history: They, like their corporate masters, are just looking for the paycheck. Everyone starts the game with a $10 million stake (a signing bonus for having a time machine stuck where the sun don’t shine) and a contract for historical mischief. It’s not like there isn’t any oversight to this enterprise, though, since the League for an Uninterrupted Continuum has hired spies everywhere to keep an eye on things and make sure the various trips back don’t turn history into a bowl of spaghetti.

As contracts and specialists come up for auction, the travelers bid to be assigned the former or hire the latter. Each job has a client (the rich person who contracted TITOR to do the dirty work), a payout for the jockey (never you mind what the client was willing to spend, just know what you’ll get paid), and one or more ways to go about securing what they want. For example, if someone wants the Venus de Milo’s missing arms you can bribe the contemporaries at the site to let you dig around in their temple or you can sneak in under cover of darkness and steal them.

Having help makes it go easier, so one can hire specialists for their charms – a cultural expert smooths things out between you and the site-keepers, for example, while the thief knows how to make off with the goods when no one’s looking. Even if one has no specialists he can hire his competitors’ workers. Your rivals can help out and make a little scratch on the side, or they can declare their specialist is a spy for the League. Eager to limit the use of time travel, the League makes life difficult for the time jockey on his mission and then disappears into the discard pile. Spies make more money for their boss than a specialist who does his job on the up-and-up, but the honest ones can be reused (and they didn’t come cheap when hired so they better pay their way before they’re allowed to “retire”).

Contracts are rated for difficulty (the more people you need and the greater the danger or the higher the profile, the tougher the task is). The jockey rolls a 12-sided die for the result. Success spells payoff while failure means either lick your wounds or try again. A good time traveler learns from his mistakes so repeated attempts are easier, but if the mission ends in catastrophe (a high roll) he’s forced to continue until the job is done (otherwise time unravels like a cheap shroud). Jockeys can only spend 15 days in the past before their atomic substructure falls apart, so the time must be spent judiciously. If they fail they die and someone else must finish the job, but that pitiable individual gets double or triple hazard pay for this thankless work.

When all jockeys agree they cannot risk another trip back or two contracts in a row come and go without a bid, everyone retires and counts money to see who wins – the highest total (among the survivors) is the victor.

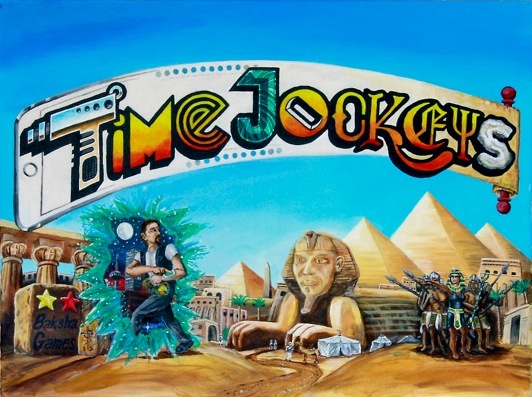

Props to Baksha Games for making cards with texture and some amount of thickness. The illustrations are sadly minimal, barely passable, unless they were done by someone still taking classes in high school in which case they’re pretty good. The box cover is almost comical. Cards aren’t text-light but they make a clear, concise job of telling you what they do, and most of the relevant rules are repeated on each of them. The rules are brief but mostly complete, with a small hole or two (is hiring out your specialist optional?) and some typos another pass by the editor could have taken care of. The counters are plain but functional, and the same can be said for the chart for tracking days spent by players.

The ebb and flow of Time Jockeys takes some getting used to – it is not intuitive – but once learned the strategies reveal themselves and the number of people trapped in a loop, dying as they try to fix a catastrophic failure, drops a bit. That’s still an omnipresent danger, so anyone who dislikes an elimination mechanic in their game is going to have a conniption if they fall prey to a few consecutive bad rolls of the dice. Indeed the whole thing seems a bit short given how few contracts one can complete before the 15-day limit is approached, but this also makes it a quick trip with little time to get bored before the tallies are made. No one need work out a grand plan when a tightly executed one works even better.

With its streamlined methods there’s less drag on your gaming time, so it makes good starting fodder or between-games palate cleanser. Time Jockeys is an excellent example of minimal game design, wherein even a few subtle changes to one’s tactics can pay off. It contains the proper amount of player interaction (read: interference) while the theme plays out nicely without a great deal of overcommitment and distraction from the temporal bells and whistles. It does more with less, allowing the design to focus on mechanics and play without bookkeeping and conflict dominating the scene. History has enough of that already.